This was originally printed in Trout Magazine Dec. 2024 issue. I’m reposting it for Autism Awareness Month.

For more of my writing, become a member of Trout Unlimited today.

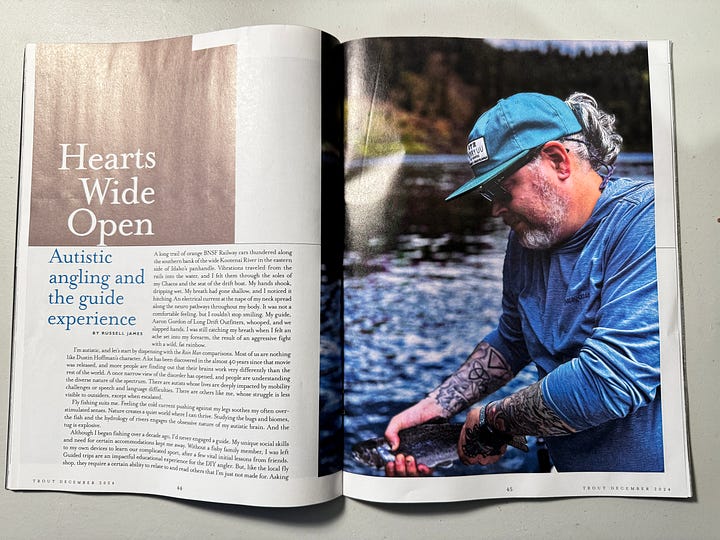

A long trail of orange BNSF Railway cars thundered along the southern bank of the wide Kootenai River in the eastern side of Idaho’s panhandle. Vibrations traveled from the rails into the water, and I felt them through the soles of my Chacos and the seat of the drift boat. My hands shook, dripping wet. My breath had gone shallow, and I noticed it hitching. An electrical current at the nape of my neck spread along the neuro pathways throughout my body. It was not a comfortable feeling, but I couldn’t stop smiling. My guide, Aaron Gordon of Long Drift Outfitters, whooped, and we slapped hands. I was still catching my breath when I felt an ache set into my forearm, the result of an aggressive fight with a wild, fat rainbow.

I’m autistic, and let’s start by dispensing with the Rainman comparisons. Most of us are nothing like Dustin Hoffman’s character. A lot has been discovered in the almost 40 years since that movie was released, and more people are finding out that their brains work very differently than the rest of the world. A once narrow view of the disorder has opened, and people are understanding the diverse nature of the spectrum. There are autists whose lives are deeply impacted by mobility challenges or speech and language difficulties. There are others like me, whose struggle is less visible to outsiders, except when escalated.

Fly fishing suits me. Feeling the cold current pushing against my legs soothes my often overstimulated senses. Nature creates a quiet world where I can thrive. Studying the bugs and biomes, the fish, and the hydrology of rivers engages the obsessive nature of my autistic brain. And the tug is explosive.

Although I began fishing over a decade ago, I’d never engaged a guide. My unique social skills and need for certain accommodations kept me away. Without a fishy family member, I was left to my own devices to learn our complicated sport, after a few vital initial lessons from friends. Guided trips are an impactful educational experience for the DIY angler. But, like the local fly shop, they require a certain ability to relate to and read others that I’m just not made for. Asking sheepish questions at the counter of my local shop while staring at my feet has never felt comfortable for me, so how could spending all day on a boat with a stranger possibly work?

Enter Aaron Gordon. I met him at a fly-tying event in Albany, Oregon, on a drippy February day. I was planning a trip to northern Idaho in July, and his company, Long Drift Outfitters, guides the Kootenai way up in the panhandle. His easy way and clear enthusiasm relaxed me, and we ended up talking for 20 minutes.

We planned a float for July 1. It would start a three-week fly fishing odyssey through northern Idaho and northeastern Oregon for me. A week before departing, Aaron and I got on the phone and talked about the intense level of preparation I needed, as an autistic angler.

I’d sent Aaron a document I developed for anyone I travel or adventure with. It contains bullet points about sensory integration, social anxiety, and what to do in the event of an autistic meltdown. Aaron asked as many questions of me as I did of him, and by the end, I was completely at ease with the upcoming float.

“You mention sensitive hearing,” he said. “There’s a lot of trains; will that bother you?” I assured him it wouldn’t and explained how to mitigate sensory and social experiences if I was wrong.

“Transition time is important,” I said. “Between catches, getting in and out of the boat. These are transitions, and sometimes I need more time than most folks.” Aaron understood.

“I tend to get overstimulated after landing a big fish.”

On the morning of the float, dawn hit northern Idaho around 4:30 a.m. After rolling around and hitting snooze a few times, I arose, brushed my teeth, and set my way to our designated meeting point. After fueling up with uncharacteristically good gas-station coffee, Aaron and I got moving towards our put in on the Idaho-Montana border. We were on the water before eight.

Aaron is an expert on the oars, and he quickly positioned us against a wall of rocks that formed the southern bank.

“They haven’t been hitting here lately, but we should give it a shot. See the drop off into deeper water, about two feet from the bank?” he asked. “Cast there.”

I did, and after a couple tosses, a cutthroat smacked the dry.

“Set!” Aaron called behind me. I moved too fast and pulled the fly away from my quarry. “Wow, great miss,” he said.

I threw more casts as we drifted slowly, and I missed a few more fish. Aaron explained that cutthroats often smack the fly before chomping down and this might be what was happening. I knew different: As an autist, the tug is charged, and I often react too quickly. I needed to breathe, give myself space to think before pulling the rod up for the set.

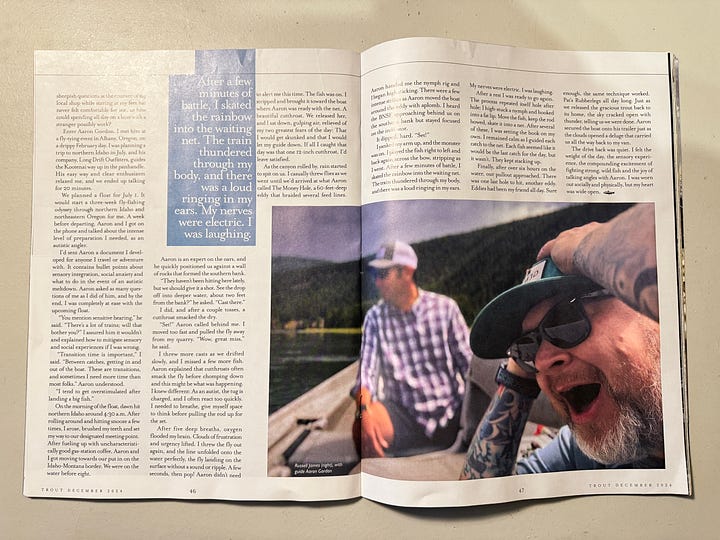

After five deep breaths, oxygen flooded my brain. Clouds of frustration and urgency lifted. I threw the fly out again, and the line unfolded onto the water perfectly, the fly landing on the surface without a sound or ripple. A few seconds, then pop! Aaron didn’t need to alert me this time. The fish was on. I stripped and brought it towards the boat where Aaron was ready with the net. A beautiful cutthroat. We released her, and I sat down, gulping air, relieved of my two greatest fears of the day: That I would get skunked and that I would let my guide down. If all I caught that day was that one 12-inch cutthroat, I’d leave satisfied.

As the canyon rolled by, rain started to spit on us. I casually threw flies as we went until we’d arrived at what Aaron called The Money Hole, a 60-feet- deep eddy that braided several feed lines. Aaron handed me the nymph rig and I began high sticking. There were a few intense strikes as Aaron moved the boat around the eddy with aplomb. I heard the BNSF approaching behind us on the southern bank but stayed focused on the indicator.

It dipped, hard. “Set!”

I yanked my arm up, and the monster was on. I played the fish right to left and back again across the bow, stripping as I went. After a few minutes of battle, I skated the rainbow into the waiting net. The train thundered through my body, and there was a loud ringing in my ears. My nerves were electric. I was laughing.

After a rest I was ready to go again. The process repeated itself hole after hole: I high-stuck a nymph and hooked into a fat lip. Move the fish, keep the rod bowed, skate it into a net. After several of these, I was setting the hook on my own. I remained calm as I guided each catch to the net. Each fish seemed like it would be the last catch for the day, but it wasn’t. They kept stacking up.

Finally, after over six hours on the water, our pullout approached. There was one last hole to hit, another eddy. Eddies had been my friend all day. Sure enough, the same technique worked. Pat’s Rubberlegs all day long. Just as we released the gracious trout back to its home, the sky cracked open with thunder, telling us we were done. Aaron secured the boat onto his trailer just as the clouds opened a deluge that carried us all the way back to my van.

The drive back was quiet. I felt the weight of the day, the sensory experience, the compounding excitement of fighting strong, wild fish, and the joy of talking angles with Aaron. I was worn out socially and physically, but my heart was wide open.

Eres una/o/e inspiracion

Congrats on getting it published, and thanks for sharing here. Great story!